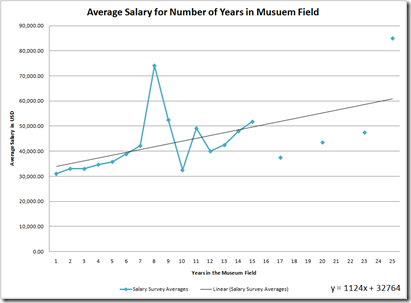

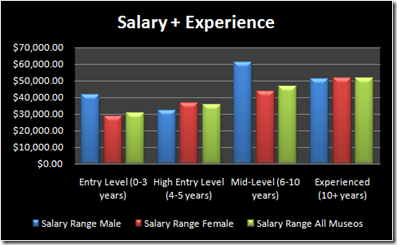

Here is the first entry in our previously announced “solutions series,” in which Museos Unite presents options (aka crazy ideas) that could be utilized by museums to remedy the whole really-low-paid-museos issue.

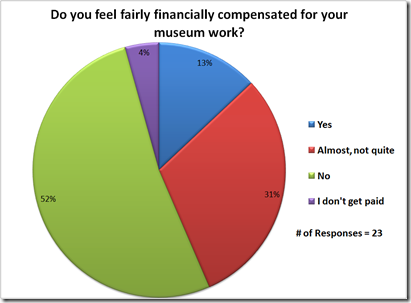

Just to review the situation: we have Museos all over the world who are coming out of graduate programs in Museum Studies--having racked up student loans—who are then forced to volunteer (unpaid), intern (unpaid or low paid), take part time work (low paid and no health care), or even get a full time job that offers a wage below the living wage. This unfortunate situation leads to Museos feeling undervalued, overworked, resentful, and angry. In some cases, Museos with a lot of potential have to leave the field they love because they cannot afford to work for free.

Yes, people sometimes have to leave a field they love and make a difficult choice to take other work, and many people point fingers and accuse these discouraged Museos of “not loving museums enough” or “caring about money too much.” Any Museo who has been following this blog since we started in August knows this argument well, and has probably gotten frustrated that the people who are making these arguments must actually be on the flip side: they must have some sort of financial support in place that allows them to throw this argument around.

This brings me to what I would call the “Robin Hood Rule.” The original idea, “rob from the rich and give to the poor,” is slightly related, but my idea is more derived from the very argument I brought up above. The two elements (1) that someone who works in museums or nonprofits should not be in it for the money and (2) that if someone works in a museum and is dedicated to its mission, then they should accept a lower pay than people in other fields because they love what they are doing. I say, let’s take this argument and instead of applying it to entry level jobs paying $25,000 , let’s instead apply it to the museum directors at the top who are making $250,000.

That’s right. Use that exact argument they are throwing down at the entry level museos and throw it back in their faces. If they love museums so much, then why do they need a high six-figure salary? Or even, in some cases, a SEVEN figure salary? Isn’t the fact that they get to be in such a great place enough? Or that they get to interact with an incredible collection, or the admiring public?

Therefore, I propose that museums cap the amount that directors make. I would say there is no need for a museum director (or any employee) to make more than $100,000. Sure, in some large cities maybe they would need a cost of living adjustment, but let’s be reasonable. If you take the extra money that person was getting and then redistribute it down to the other salaries, you’d never have anyone starting at a salary below the living wage. Let’s say the lowest salary able to be offered would be $36,000 to someone with an undergrad degree and $40,000 to someone with a grad degree. Those are very fair starting salaries.

“But then the best people would leave the field or go to other museums!” you say. Oh really? If the money is so important to them, then should they be in charge of the museum? Just think. There are hundreds of applicants for a entry level museo job these days, which is why they can afford to offer low pay. There is ALWAYS someone who will work at that lower pay. How many great Museos do you think would be willing to say “heck yeah, I’d be a museum director for $100,000!” And then if they decided they wanted more money after a while, they could go ahead and leave the field, thus opening the position up to new talent who is again willing to accept a very fair wage.

For example, let’s use the biggest museum in my home city, The Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA). The director made $338,873 in 2008 (guidestar.org). If we take that down to the proposed $100,000 then we have a stunning $238,873 to redistribute. Now, if I add up the 8 highest paid employees (who all make over $100,000) and limit all of them down to $100,000, then guess how much money we have to throw around?

$771,352. From eight people.

If we assume there are a bunch of people at the bottom making $20,000 (which is probably not that far from the truth), then we could raise their pay up to $40,000 with this money… dramatically changing their lives from living below the poverty level to having a very good starting salary. How many of those low paid Museos could be helped with the extra [excessive] pay from the top Museos?

38 people could go from $20,000 to $40,000.

Even more dramatically, let’s delete the above option and just do this one. How many unpaid interns could be hired at a starting salary of $36,000?

21 people could go from unpaid to making $36,000.

And all of this because 8 people took pay cuts that limited them to a wage that's incredibly reasonable for living in Philadelphia.

There are actually many nonprofits with a structure like this. I talked to a man last month who runs a nonprofit, and he explained that everyone in the company makes between $40,000 and $90,000, no more and no less. No one is struggling to live, and no one is buying a yacht with golden toilets.

How can museums be a medium for discussion of social fairness if they are operating just like any huge, multi-national corporation instead of the nonprofits that they are? Ethically managed companies often have limits on what senior management can make, so why don’t museums join in?

----------------------------------------------------------------

NB – I know that for many small museums, no one is making even $40,000. I know this argument doesn’t apply to them. I’m going to think more on how to fix those things, but I think if the big museums started making changes, there would somehow be a trickle down effect. Does anyone have any ideas about that?